A while back, as part of a series of fascinating studies of perception in chess, Simon and Chase showed a chessboard to people with several degrees of chess expertise, for very brief moments, and asked them to reproduce the position of the pieces in the board they saw, using a second board and set of pieces.

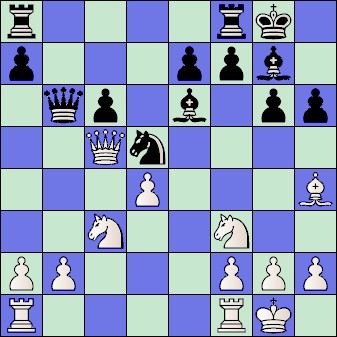

For half of their runs, they used reasonable mid-game positions, such as the following:

For these cases, expert chess players were able to reproduce the position faster and more accurately than novice players, and they needed fewer ‘peeks’ at the original board too.

Now, for the second half, they used positions with about the same number of pieces than the first, but the pieces were placed at random cells of the board. Here’s an example of my own:

If you don’t know chess, this image will be just as cryptic as the previous one. You would probably take as much time to reproduce it, and make as many mistakes too.

If you’re competent at chess, however, the second image will feel ‘wrong’. It will make no sense to you. If you’re an expert, it may even look like an abomination. And if you were to try to reproduce the position, you’ll lose your advantage over novices -you’ll perform just as slowly and inaccurately as them, perhaps even worse.

That’s what Simon and Chase discovered. Furthermore, they found that experts tended to add clusters of pieces at once. They conjectured that, when looking at a game position, a chess master does not see the same things mere mortals see. Somehow, after years of training, they get used to identify structural patterns and interactions between pieces. And they learn to exploit their ever-expanding knowledge base at will, almost unconsciously, so that when shown a ‘reasonable’ position they grasp it effortlessly, but when shown something that doesn’t make sense, their elaborate mental model is useless to understand it. In my previous example, for instance, I (with a merely competent chess knowledge) can identify these clusters:

Meanwhile, a novice does not have access to this wealth of information. They don’t see the clusters and structures experts see, and so they have to work out the position piece by piece, no matter the structure’s degree of normalcy.

This phenomenon happens all around us, in any domain where expertise plays a role.  For example, I’ve always been confused when doctors point to abnormalities in radiographies that I simply do not see. On the other hand, expressions such as, say, a simple quadratic function, are instantly recognizable for me -I have a visual image that goes hand-in-hand with the expression, and I’ve seen and applied it enough that it probably means to me more than what it means to someone with a high school level math education.

For example, I’ve always been confused when doctors point to abnormalities in radiographies that I simply do not see. On the other hand, expressions such as, say, a simple quadratic function, are instantly recognizable for me -I have a visual image that goes hand-in-hand with the expression, and I’ve seen and applied it enough that it probably means to me more than what it means to someone with a high school level math education.

Once a community of experts starts to discuss their domain, they will inevitably create words, or assign new meanings to old words, to refer to concepts they use commonly and for which their natural language falls short. This development of terminology is a sign that the domain is becoming mature and well explored. To stick with chess, for example, players will talk about controlling the centre, forking, and open columns naturally. Game discussions frequently use these loaded terms, so representations that use them are economically convenient. However, this practice raises the entry barriers for newcomers (as anyone who has listened to doctors discuss would agree).

Incidentally, it is sometimes also the case that a novice sees things that an expert will not. The expert assumes things that, in strange cases, may not be true. For example, consider the following chess retro-puzzle from Raymond Smullyan:

Black has made the last move. What was it, and what was White’s previous move?

The puzzle, as it stands, has two possible answers. Try to figure them out. I discuss them in the next two paragraphs, so skip them if you just don’t care!

For both answers, it should be obvious that Black’s last move was with the king -no other piece available- and from the cell below of where it currently is (it cannot come from the right because that would imply an impossible check from the white king). This means it escaped from a bishop check. But how did the bishop get to that seemingly unreachable position in the first place? The first answer is that the check was revealed by another piece -but it would have to be a piece no longer on the board. The only possibility, then, is for a white knight to jump (from b6) to the board’s corner, uncovering the check. The black king then escaped the check by capturing the knight, leading to the current position.

The second answer depends on realizing that, perhaps, we’re not looking at the board from the perspective of White, but of Black. If that’s the case, we can explain the bishop’s placement as a promoted pawn! A white pawn moves to the bottom row, gets promoted to a bishop, checks, and the Black king escapes to the corner of the board.

Some people have a hard time seeing the second answer. It runs against two standard assumptions of chess -that White’s side is displayed on the bottom, and that when we promote a pawn we promote it to a piece of greater power than a bishop. However, if you’re not familiar with these conventions, but know enough of chess to understand how pieces move, you may even outperform an expert chess player (being, in Dan Berry‘s terms, a “smart ignoramus“, a person whose ignorance of a domain, paired with a sharp intelligence, leads him or her to ask valuable questions that experts would not think of asking.

I think I’ve abused of chess long enough. In the end, what I want to do is remind us that people see, literally, different things in the same representation. Their understanding of it, and their potential with it, will depend on their domain and language expertise. Meaning is in the mind of the beholder. And so representations are not just useful or not -they are useful for a particular person, or type of person, to accomplish a particular task.

Next in the series: How to search for books in a library that has no index, and Borges’ Library of Babel.

ADDENDUM, April 2016: I created the chess images above and I release them with a CC0 license to the public domain. Feel free to use them!

Jorge,

I particularly enjoyed this post. I am not a chess expert but have the basic knowledge to understand what you are saying. Reproducing positions on a chess board reminded me of Piaget´s mental models: Learners are more likely to understand information that can be assimilated in an easier way and that occurs due to previous cognitive structures.

The same example applies to memory, since retention it is triggered by significant relations. In your example, experts can relate to their previous experience, the knowledge of the board and the way pieces move. If “normal” people make the pieces/positions significant to them, their retention will be superior than just trying to remember.

Last comment is about those people who can elicit names of objects from an audience and then repeat them in order or backwards. As far as I know they create a story in their minds (a meaningful story) including each of these objects and that´s how they remember.

Do you think this might be related to what you´re trying to communicate?

Glad you liked it! Yes, these ideas are related to Piaget’s development process (and to Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development).

Regarding your last point -people that form stories to remember sequences of objects: it’s an interesting case. It’s probably an instance of the structure-finding skill I described above, but I’m not really sure. However, it definitely has to do with their (learned) skill of creating structure where none is apparent. Such a person would have a much higher retention capacity than me, and so would not need as many external memory aids as myself.

One interesting point that you made is that experts develop a common language. But this is applicable not only to computer science or other professional fields, but also to human relationships. You can see how people from Mexico in Canada use and reuse incorrect expressions like ‘hacer un poco de networking’ what means nothing, but here the phrase acquires a relevant meaning. The same clusters of language occurs within regions, so, even when you are in the same country speaking the language and you move to another region, people would know that you are not from there just because the language you use and how do you call things (accents set aside).

True. This reminds me I have a much harder time explaining my research in Spanish than in English, even though Spanish is my first language. Since I deal with topics written mostly in English, talk to everyone at the University in English, and take notes / write in English, this is the language that comes naturally to me when dealing with the topic. So, frustratingly, I end up speaking Spanglish if I try to translate.

Jorge,

I thought about your post for a while, and it brought to my mind another issue, not so much related to your chess story. I was at a friend’s house two days ago, and he couldn’t find the remote control for some device (probably the tv). The absurd thing is, there were about 8 remote controls “roaming” around the room, on the coffee table, hidden under the sofa, and so on.

My point is, the hiddenness in plain sight can also relate to clutter (i* comes to my mind), not just to expertise of the beholder.

Absolutely. In fact, that has a lot to do with my next post on the series, which I’ll get to as soon as I finish writing a paper 🙂

i* (a language to model goals and dependencies of agents in a domain) can be very cluttery for medium to large domains, but I fear it is more the norm than the exception.

Well, luckily for me, the remote control issue was solved, at least partially, with a Universal remote. However, the clutter caused by modeling languages such as i* is not solved yet. Solve that … and you’ll have earned your phd 🙂

Also, if you can solve the problem of finding a good apartment in tel aviv area within 8 days, you’ll have earned my eternal gratefulness.

Cheers 🙂

“Also, if you can solve the problem of finding a good apartment in tel aviv area within 8 days, you’ll have earned my eternal gratefulness.”

There are some problems that not even the brightest minds can tackle.

I really like the retro puzzle!

I think i have a third solution as well: suppose the white pawn didn’t come from b7, but he came from c7 where he took a black piece on b8 and promoted 🙂

That would work too, Koen!

Hi Jorge! And Hi, Koen!

Koen, although the scenario you described is theoretically possible, it is highly unlikely. The black piece would have to have been either a queen, rook, knight, or bishop. Had it been any of the first three, it would have been busy teaming up with the black king and attacking the white king. If it was a bishop, it would have taken at least one of those pawns, and thereby escaped the other (had it somehow allowed itself to be trapped in such an unfortunate position in the first place). The other two solutions are more likely scenarios…. Still, it is possible 🙂

Hi Jorge,

I am wondering where the 4 chess board images came from? I would like to find the original source? Thanks!

Hi Kathryn,

Replied over email, but just in case: I’m the source, and I’ve added a note at the end of this post to clarify that the images are now in the public domain–happy re-using!